Let’s Talk Turkey: The Untold Story of Ontario’s Wild Bird Comeback

It started off with a trade. Ontario agreed to provide moose to Michigan, river otters to Missouri and Nebraska, and gray partridge to New York. In return, Ontario would receive Eastern Wild Turkeys.

Today, Turkeys are abundant across Ontario, but just 45 years ago, they were all but gone.

But if you look around today, you wouldn’t be able to tell. Wild Turkeys are now one of Ontario’s most successful, but little-known, conservation success stories.

“The reintroduction of wild turkey has been a huge success and proves how restoration efforts can have extremely positive outcomes for biodiversity and our hunting heritage.”

-Lauren Tonelli, Resource Management Specialist, OFAH, OFAH.org

Ontario is home to only one species of wild Turkey, known as “Misisse” by the Ojibway First Nations, meaning “big bird”, the Eastern Wild Turkey. (Meleagris gallopavo silvestris)

Archaeological evidence suggests wild Turkeys were present in Ontario as early as 900 AD.

In 1824, wild Turkeys were a common sight, with flocks of eight to ten birds frequently observed in various parts of Upper Canada, now known as Ontario. “Turkeys were still a prominent game bird in the district in 1880. Turkey Point on the north shore of Long Point bay was doubtless given its name after this wild bird, which at one time frequented its swamps and woods.” A 1931 Royal Ontario Museum of Zoology report noted.

Signs of population decline began to emerge in the 1880s.

In 1883, Ontario enacted prohibitions on the export of Eastern Wild Turkey carcasses. Later in July of 1886, the species was protected throughout Ontario, with a fine of $5 to $25 per bird or egg, approximately $155 to $774 in today’s value.

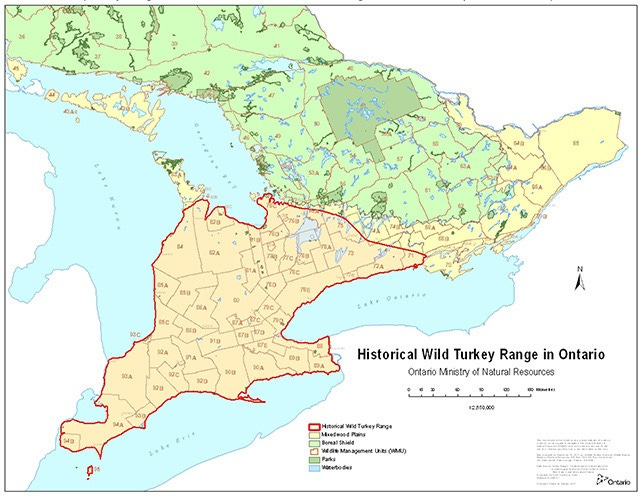

But by 1904, it was the opinion of the Ontario Chief Game Warden that no Wild Turkeys remained in the province, likely as a result of a combination of agricultural clearing and overhunting.

Early attempts to reintroduce the Eastern Wild Turkey to Ontario before the 1950s relied on pen-raised, or captive birds. These populations often struggled to sustain themselves, requiring supplemental feeding during the winters, and ultimately failed to establish a lasting presence.

In the 1980s, renewed efforts began to reintroduce the Eastern Wild Turkey to Ontario, with advocates lobbying the provincial government. New research had shown valuable insights into the survivability of wild-caught turkeys that were relocated to new habitats.

The Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters (OFAH) played a pivotal role in driving these reintroduction efforts, lobbying the provincial government for their return.

Eventually, the Ministry of National Resources and Forestry (MNRF) created the Wild Turkey Reintroduction Steering Committee to oversee the planning, which included representation from the Ministry, Ontario Naturalists and the OFAH.

It started off with a trade. Ontario agreed to provide moose to Michigan, river otters to Missouri and Nebraska, and gray partridge to New York. In return, Ontario would receive Eastern Wild Turkeys, which would be released at 275 sites across the province. This began the efforts to reintroduce the Eastern Wild Turkey into Ontario.

The first Eastern Wild Turkeys released in Ontario, in March 1984, were transplants from Missouri; 27 birds in total were introduced into the MNRF’s former Simcoe Management District. (WMUs 68 and 71 in the present time)

From 1984 to 1987, the MNRF continued to receive and release 274 eastern wild Turkey's from Missouri, Iowa, Michigan, New York, Vermont and New Jersey.

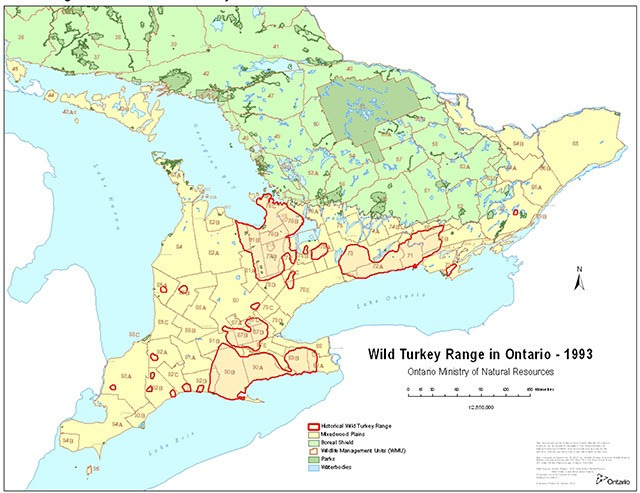

The Eastern Wild Turkeys reestablishment was well underway, with controlled hunting seasons opening in select wildlife management units where Turkey populations had become well-established. The Wild Turkey Reintroduction Steering Committee was disbanded in 1986, with its goal of returning the Eastern Wild Turkey to Ontario being fulfilled.

A wild Turkey management workshop was held in Peterborough with representatives attending from the Ministry of Natural Resources, Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters, National Wild Turkey Federation, and the states of Iowa, Missouri, Vermont, New York, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. Armed with new information, in 1987, the Ontario Wild Turkey Working Group (WTWG) was formed as a successor to the Wild Turkey Steering Committee to implement what was learned during the turkey management workshop.

By the winter of 1994, 1,000 Eastern Wild Turkeys had been successfully released into Ontario. While they had begun to establish themselves, their range was still incomplete, with some parts of their historic territory remaining unoccupied. The 1994 Wild Turkey Management Plan for Ontario aimed to expand the turkeys into these areas, with the goal:

“to contribute to the diversity and health of ecosystems and associated wildlife populations and habitats by sustaining and increasing Ontario’s wild turkey population for the benefit of the people” (1994 Wild Turkey Management Plan for Ontario)

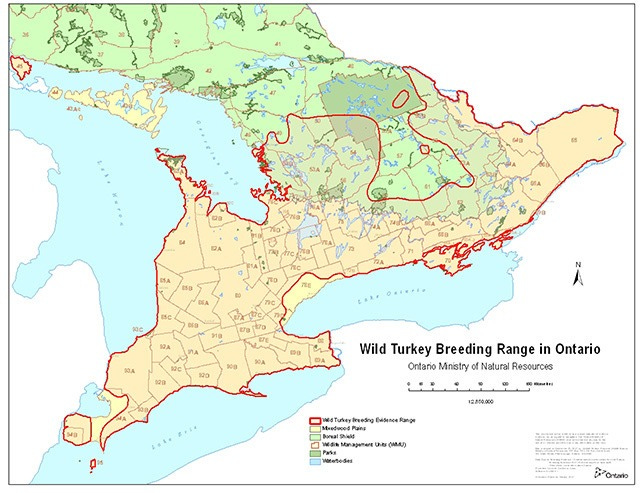

As the reintroduction efforts progressed, the Eastern Wild Turkey population in Ontario steadily grew. By 2007, the population had reached an estimated 70,000 birds, fully encompassing its former historic range and expanding beyond it.

Today, the Eastern Wild Turkey is thriving in Ontario, thanks to the dedicated efforts of the OFAH and the MNRF. In recent years, populations have been stable and high enough to allow for a Fall hunting season. Although its a second hunting season, this is a good sign for the Eastern Wild Turkey in Ontario.

“As turkey populations continue to grow in the province, they are beginning to expand into new WMUs. This is great news and more evidence of how successful the reintroduction effort was.”

-Lauren Tonelli, Resource Management Specialist, OFAH, OFAH.org

With improved wildlife management practices and stricter hunting regulations in place, the Eastern Wild Turkey is well-positioned to continue gracing Ontario’s forests and fields for generations to come.

Sources

Morris, Zoe; White, Christine D.; Hodgetts, Lisa; and Longstaffe, Fred J., “Maize Provisioning of Ontario Late Woodland Turkeys: Isotopic Evidence of Seasonal, Cultural, Spatial and Temporal Variation” (2016). Earth Sciences Publications. 18.

https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/192023932.pdfWintemberg, W.J. 1919. “Archaeology as an Aid to Zoology.” The Canadian Field-Naturalist 33 (4): 63--72. https://doi.org/10.5962/p.337897.

Snyder, L. L., E. B. S. Logier, and Royal Ontario Museum of Zoology. 1931. A Faunal Investigation of Long Point and Vicinity, Norfolk County, Ontario. [Toronto: Royal Ontario Museum of Zoology]. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/36300601.

Alison, R. M. 1976. “The History Of the Wild Turkey in Ontario.” The Canadian Field-Naturalist 90 (4): 481--485. https://doi.org/10.5962/p.345105.

Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters. (2021, December). Better hunter reporting in Ontario drives new turkey hunting opportunities. Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters. https://www.ofah.org/insider/2021/12/better-hunter-reporting-in-ontario-drives-new-turkey-hunting-opportunities/

Follow the Field & Shutter Press

Instagram | YouTube | BlueSky

Have a tip, story idea, event, or want to appear as a guest column? Contact us.

I had heard that Montréal was having uptick in wild turkeys, but I didn't know it was to that extent, thanks for sharing!

Glad to see the reintroduction has been so successful, they are really interesting birds. On a similar note, the urban turkey population has been growing a lot up here in Montréal. A few years ago there was a famous turkey named Butters who went viral and had police assigned to try to protect him from being hit by cars, and last year there was a mother with 2 baby turkeys at my community garden. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/wild-turkeys-montreal-1.7145620