Young people will speak up in court after leaders stayed silent about Ontario development bill

By Sonal Gupta, a Local Journalism Initiative Reporter with Canada’s National Observer.

This article was originally published by Sonal Gupta, a Local Journalism Initiative Reporter with Canada’s National Observer.

Ramon Kataquapit says it was the silence from his First Nation leaders after Ontario introduced legislation to fast-track land development, that ultimately rallied other young people in his community to take charge of their future.

From Attawapiskat First Nation, Kataquapit, 23, said others in Treaty 9 also felt frustrated and excluded from decisions impacting them after the province introduced Bill 5. And “that caused a lot of the youth all at the same time almost to spark into action,” he said.

This week, Kataquapit is taking their fight into court.

In a motion filed Monday, he and Michel Koostachin, who is also a member of Attawapiskat First Nation, seek to intervene in an existing lawsuit launched by nine First Nations shortly after Bill 5 passed.

While nine First Nations are already challenging the legislation on the grounds it violates treaty rights and removes environmental protections across Treaty 9, Koostachin said the case must also include the lived experiences of grassroots people: youth, elders, knowledge keepers and community members who are most vulnerable to the changes Ontario is trying to introduce.

Treaty 9 covers much of northern Ontario, stretching from the boreal forests along the Hudson and James Bay coasts to the mineral-rich interior known as the Ring of Fire.

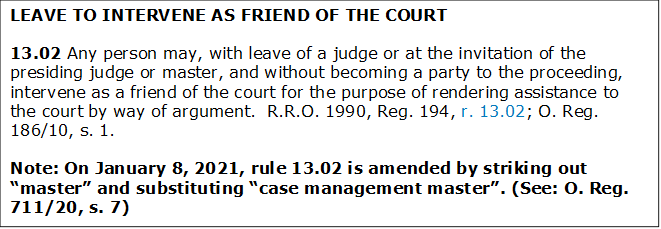

Kataquapit and Koostachin are asking to participate as friends of the court, where they could share legal arguments but wouldn’t be allowed to bring new evidence. The motion states they plan to address three key points: how reconciliation connects with Indigenous legal traditions and treaty obligations, how international standards, such as the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, should shape provincial decisions and whether Bill 5 creates discriminatory effects by exposing some communities to greater environmental harm.

Koostachin describes a long and growing disconnect between elected chief-and-council structures and the community members who continue to live by what he calls Indigenous natural law — a system of responsibilities and teachings that predates the Indian Act. He said elected leadership “follow the Indian Act,” which changes every election cycle, while community members must live with the long-term consequences of industrial development.

He said the legal fight cannot be understood without acknowledging those who rely on river systems, peatlands and wildlife for food, ceremony and teachings. The vast northern peatlands — waterlogged and mossy wetlands that store enormous amounts of carbon — stretch across the Hudson and James Bay lowlands, forming one of the largest intact ecosystems of their kind on Earth. “We’re the ones that travel our waterways,” he said. “We have ceremonial sites. We have burial sites that we have to respect.”

He pointed to ongoing social pressures, including housing shortages, addiction crises and limited services for youth and families. Rapid development, such as the proposed mining linked to the Ring of Fire, could intensify those strains.

Even though the proponents of development promise jobs and prosperity, past projects have offered little long-term benefit to their communities, he said. He pointed to the De Beers-owned Victor diamond mine as an example: “We went to sweep the floors… we didn’t manage what was up.”

A larger movement is happening across the region where many other First Nations members oppose the bill and demand a voice in decisions affecting their homelands.

In his community, Kataquapit helped create a youth-led movement called Okiniwak to bring young people into political conversations. It gave them a direct platform, Kataquapit said, “without having to go through any organization, any chief, anything that might be able to get misconstrued.” The group took the movement “all over Ontario,” hosting workshops, rallies and lectures to raise awareness and mobilize communities.

Kerrie Blaise drafted the motion and said this intervention is supported by a coalition of allies and nonprofits, including Ontario Nature, to overcome financial and legal barriers that typically prevent such participation.

“It takes an all-hands-on-deck approach to make sure that you have the funding, the resources, the capacity to do this work. No one is profiting from this, this is grassroots advocacy at its core,” Blaise, who is founder of Legal Advocates for Nature’s Defence and an environmental and Indigenous rights lawyer, told Canada’s National Observer.

Too often, the burden of opposing extractive development has fallen disproportionately on First Nations, who face limited resources within a system that already restricts their ability to make decisions, said Shane Moffatt, campaigns and advocacy manager for Ontario Nature.

Moffatt said environmental groups nationally must step up as allies without dictating outcomes to Indigenous communities. “At the end of the day, it’s really important that Indigenous Peoples are able to make the best decisions, and they have the right to make the best decisions for their communities in the context of a colonial system, which imposes significant limitations and restrictions and inequities on those communities,” he said.

The impacts of accelerated development will first affect territories where communities rely on healthy waterways and peatlands. Disrupting them, Kataquapit warned, could release sequestered carbon and further damage already stressed river systems. Residents along James Bay, he added, “know the facts of having pollution within waters,” pointing to long-standing concerns that followed the Victor mine.

Kataquapit is one of the first in his family not to attend residential or day schools, yet the legacy of those institutions continues to shape his daily life. Reconnecting with the land, he said, has informed his view that decisions about Treaty 9 must look beyond short-term development and consider the future of the territory and the people who rely on it.

He said the costs of Bill 5 will fall on northern youth, not policymakers. “We will be the ones that have to deal with the consequences.”

Follow the Field & Shutter Press

Instagram | YouTube | BlueSky

Have a tip, story idea, event, or want to appear as a guest column? Contact us.